Levers for Agent Coordination

A high-level framework for agent coordination, levers for key coordination dynamics, and some initial prescriptions for what to coordinate around

BLOGPROJECTS

9/14/202529 min read

Importance of Agent Coordination

The future will contain more numerous agents with greater levels of absolute power as well as unprecedented power differentials. This makes transformation inevitable, contentious, strains our institutions and, in lieu of thoughtful collective action, is likely destabilizing. This critical inflection point in our societies necessitates clear thinking about the complex problem of agent coordination.

At the center of this transformation is the accelerating emergence of artificial agents—future systems with the capacity to act autonomously, scale influence rapidly, and reshape institutional behavior. Their impact is already foreseeable in projected multi-trillion dollar total addressable markets (TAMs), and tangible in the deployment of early humanoid robots, autonomous vehicles, and in increasingly capable virtual AI assistants. These technologies are not simply tools. They are becoming actors—participants in multi-agent ecosystems where incentives collide, align, and evolve in real time.

At the same time, globalism appears under threat, as state-level actors such as the US, China, and EU work actively to reduce interreliance while hostility in the form of cyberwarfare, strategic trade maneuvering, and armed conflict increase, threatening the relative stability and peace enjoyed by many in the post WWII era.

Our long and storied history reveals the deep difficulty of the coordination problem at scale. Time and again, civilizations have fractured under the weight of misaligned interests, coercive power, and runaway competition. Now, the accelerating pace of technological progress—and the dawn of an AI revolution—intensify both the pressures and the stakes. Civilization’s long-term stability depends on our ability to identify threats and negative externalities in multi-agent environments, respond with targeted countermeasures, and coordinate deliberately. The desirable endgame is neither uniformity nor hegemony, but a system capable of sustaining prosociality, liberty, and fairness, with mutual dignity, and respect for all, to the maximum attainable extent.

To pursue that future, we must treat agent coordination as the defining systems challenge of our era—one that demands the full force of our engineering and governance expertise. Meeting it will require breakthroughs in both technology and civics, and the deliberate construction of new infrastructure to match. This essay explores qualitatively some dynamics by which multi-agent systems—human, artificial, and institutional operate. I discuss the levers that these dynamics point to which can be used to shape incentive landscapes, then I make concrete claims about the type of future we ought to build.

What is an Agent?

As a first step, let us clarify the foundational class of entities at the center of this analysis: Who—or what—is an agent, and what can be said about agents in general?

Agents possess three key capacities:

Values — underlying standards or evaluative principles that shape what outcomes they regard as desirable.

Goals — particular outcomes, singled out from those values, that the agent actively pursues.

Power — the capacity to act on the world in ways that bring those outcomes about.

It is this combination—values, goals, and power—that distinguishes agency as a unique and consequential category. We see immediately then that human beings are agents. Many animals clearly qualify as agents as well. And increasingly, so do artificial systems. In the near future, we will share our environment with AI agents that act, learn, and optimize across domains—perhaps faster than humans can, perhaps more flexibly.

Agents, naturally, can be composed of non-agentic parts, as neurons compose a mind. And agents can themselves compose larger agents: families, corporations, bureaucracies, and states. These composite agents exhibit emergent behavior and often act with strategic coherence, even if internally fragmented.

Agents need not be perfect reasoners. They may operate under limited knowledge, bounded rationality, or conflicting internal drives. But it is precisely this variability—in reasoning, awareness, and coherence—that makes multi-agent systems so dynamic, and so difficult to coordinate.

Here I focus on powerful, intelligent agency—particularly those systems, human or artificial, whose capacity to influence the world is rapidly increasing. For the first time in history, we face the prospect of scaling intelligent agency itself. And with it, we inherit the challenge—and the responsibility—of designing a world where many such agents can coexist, compete, and cooperate without collapse.

The Power of Intelligent Agency

To illustrate the distinctiveness of intelligent agency, let’s imagine a simplified world—a tournament of rock, paper, scissors. In this world, non-agentic players follow fixed strategies: rocks always play rock, papers always play paper. Agents, by contrast, observe the pattern, learn the rules, and adapt. In this way intelligent agents find rocks, papers, and scissors trivially defeatable. They quickly learn the only real competitors are the others like them, those who adapt, revise, and respond in kind.

This adaptability is the signature of intelligent agency. While nature unfolds according to fixed laws, agents learn those laws—and respond. In the history of life on Earth, human survival has often been precarious. Certainly it is possible to backslide, to collapse, to by some misstep or misfortune go extinct. And yet, as long as intelligent agency persists—learning, adjusting, optimizing—its influence, its power compared to the non-agentic universe grows. Over time, you would expect it to shape not only its own fate, but the structure of its environment.

One might best forecast the far future by identifying two classes of parameters: the laws of physics (what actions are possible), and the desires of agents (what outcomes are sought). If something is physically achievable, and if agents who want it endure, then—given time—they will likely bring it into being.

Agents vs. the Universe

To the extent that there are coherent endgames in the game of agents vs. the universe, betting on agents to eventually overcome all surmountable obstacles is a wager I’d take. Most agents have reason to preserve their agency—continued existence is instrumentally valuable for nearly any goal. Humans have pursued this through reproduction, legacy, and increasingly, through technology. If agents succeed in persisting, then over the long arc of time, we should expect them to accomplish remarkable things—mastering their environments in unprecedented ways. They might harness the energy of entire stars with Dyson swarms, construct stellar engines and Matrioshka brains, or seed the cosmos with self-replicating probes.

Many a physicist is fond of a cheeky little razor that divides future projects into two categories: either your brilliant device is doomed—ie. ruled out by the laws of physics—or it’s “mere engineering,” which is to say, permitted by physics and thus, in some sense, trivial—perhaps even inevitable.

Of course, this distinction elides the vast, thorny terrain of engineering in reality—the thousand interlocking challenges that stand between theory and execution. Still, the razor captures something true: that in a world governed by fixed laws and navigated by adaptive agents, effort compounds. Iteration works. Failures inform. Designs evolve.

Today we are small, and vulnerable. A stray supernova, asteroid, or errant gamma-ray burst might still do us in. But if given the time and the will, we would master them too—as we once mastered fire.

We must recognize that the previous state of play no longer reflects the magnitude of the challenges facing civilization today—nor those looming just ahead. When agents adapt to overcome some obstacle in nature, the universe does not adapt in return; it continues playing its part according to its fixed laws. But when we adapt to other agents, they adapt back. The result is a continually shifting landscape—dynamic, recursive, and rich with both opportunity and risk.

Challenges of coordination evolve with us, growing in complexity as the collective share of agential power comes to dominate over the base equilibria of a younger, less awakened universe. You see this pattern even in small, bounded worlds—like that of a board game. At first, the challenge is to learn the rules: what actions are available, what outcomes they produce. But once the rules are known, future difficulty flows from the presence of other agents—their strategies, their counter-moves, the branching game tree you form together.

If we are to endure—not only for the long haul, but even to live well in the present—we must confront the deep challenge of agent coordination. It is the substrate on which every other aspiration rests.

High Level, Directional Approach to Agent Coordination

Recognizing the stakes implicit in the long-term stability of multi-agent systems, some progress has been made under the banner of agent foundations—a research effort to formalize how idealized agents reason and act under uncertainty. This work draws from rich traditions in decision theory, game theory, social choice theory, Bayesian epistemology, and theoretical computer science. I’m a fan of this line of inquiry, but I do not attempt it here.

Instead, I aim to gesture directionally—toward salient dynamics shaping coordination among agents, and toward a conceptual foundation for what robust multi-agent systems might require. I believe the work of coordination will be advanced less by theoretical completeness than by distributed iteration—through the public discourse we elevate, the policies we enact, and the technologies we choose to build. In the end, the systems we get will reflect the choices we institutionalize, not just the axioms we prove.

Why We Need This Approach Now

We will not have solved agent foundations by the time robust agent coordination is required. Indeed, we already suffer from global coordination failures: arms races, climate change, pandemic response failures, growing antibiotic resistance, etc. The complexity and urgency of these problems, compounded by the emergence of autonomous agentic AI systems, demands a clear, directional vision for improving coordination.

Fortunately, we don’t need to solve every foundational question in epistemology or decision theory to make progress. The great advantage of agency is adaptability. If you're launching a rocket to the moon, you’d better get the math right—small errors at the outset compound over time, and nature punishes imprecision. But if you're driving from D.C. to San Francisco, you don’t need a perfectly preplanned trajectory. You need a compass heading—go west, young agent—a rough map, and the ability to course correct along the way.

Salient Properties of Multi-Agent Systems

Operating Assumptions

Agents tend to desire persistence.

While some agents may hold values that do not prioritize survival, such agents are less likely to persist. Most agents benefit instrumentally from continued existence—not just to avoid death, but to preserve their agency: their ability to choose goals, pursue values, and exert power over the environment. Insofar as an agent cannot ensure the persistence of its self or values alone, it will have incentive to coordinate with others—whether to gain an edge over non-agentic threats or to safeguard against the actions of other agents. Thus the desire for persistence offers substantial common ground, even across agents with divergent ends and this forms an impetus for the formation and maintenance of a society.

Agents can cooperate to mutual benefit.

There exist win-win cooperative structures, and agents are capable of recognizing and participating in them. Cooperation is not a naive ideal—it is a game-theoretic attractor in many settings, particularly when trust, communication, and aligned incentives are present.

Agents can compete resulting in mutual benefit, one sided advantage, or double downside

Competition may result in mutual benefit, one-sided gain, or mutual harm. That is, win-win, win-lose, and lose-lose outcomes all arise in competitive environments, depending on the circumstances and rules of interaction.

These observations give us a sense of common incentive (i.e. the preservation of agency) and of interaction outcomes, but they don’t determine how agents will behave in any particular system. To understand the dynamics of coordination, let’s look in depth at three key properties: alignment windows, coherence, and power differentials. Here, I’ll create a framework/picture for the conceptualization of these dynamics. To do so I’ll play fast and loose with vector space and do not attempt a rigorous definition or measurements but I believe the rough picture is nonetheless useful for identifying interventions to enhance agent coordination.

Alignment Windows

Coordination is easiest among agents whose goals are closely aligned. When values diverge, tension arises; when values directly conflict, cooperation becomes difficult or impossible. AI researchers have explored this in the context of alignment between artificial and human agents, but the concept generalizes: alignment matters wherever agents interact.

To make this more concrete, we can visualize agents in a high-dimensional value space, where each agent is represented as a vector pointing from the origin toward its preferred outcomes. The origin represents total neutrality, perfect ambivalence; axes correspond to value dimensions—libertarianism vs. authoritarianism, individualism vs. collectivism, as well as myriad values like personal social standing, or enjoyment of exploration, and tasty food. Importantly, the space is high dimensional. Your valuing cities of Brutalist retrofuturism, unlimited marionberry crumble, and songs by Dolly Parton are all representable there, and in combination they capture the full set of multifaceted values that an agent can conceivably express. When making practical use of this tool we might focus on a particular subspace or axis eg. consequentialist vs deontological. Alignment between agents then means that their value vectors point in similar directions—perhaps fully along some dimensions, and only partially along others.

Consider Altruistic Alice (a human) and Bob-4.1 (an AI model). If their vectors point to precisely the same direction in value space, they are fully value-aligned—they care about the same things to the same degree. But alignment can also exist in projection: they may overlap along certain dimensions while differing on others. For example, both might prioritize fairness and flourishing, but Alice weights individual liberty more heavily, while Bob favors collective stability; Alice wants a dog park, Bob would prefer if the city built a library.

Further, despite this partial alignment in value space, they may still diverge sharply in their choice of actions. Even perfectly value-aligned agents can disagree on how best to realize shared ends—due to differences in information, or reasoning. In such cases, we can say they are aligned in value space but misaligned in goal space: the objectives they pursue to realize their values differ, sometimes enough to produce conflict despite shared intent.

From this we can also see that perfect value alignment is rare, Alice and Bob will have difficulty agreeing on the same ideal terminus. Alice would need to care about Bob and the things Bob loves exactly as much as Bob does, for starters. Fortunately, this is not necessary. What matters is whether two agents fall within the same alignment window—the range of values that can coexist without one agent’s goals precluding the other’s. Alice and Bob need not prefer all the same things to the same degree; they need only determine that some world in which Bob is happy is not a world in which Alice cannot be happy.

Alignment windows are not fixed—they are shaped over time by the agents within a system: individuals, coalitions, and institutions. Cultures emerge, are contested, and evolve. In some eras and societies, the alignment window is broad, tolerating a wide range of values and lifestyles. In others, it narrows, and divergence is harshly punished. These windows define the boundaries of peaceful coexistence in any multi-agent system. Agents whose values fall within the prevailing window form the in-group—bound together by shared norms that sustain trust and enable cooperation.

Cultural forces often act to constrain agents within the alignment window, reinforcing dominant norms. But agents also push back—forming countercultures that challenge the boundaries and, over time, may reshape them. The result may be progress, regression, or simply change, depending on one’s frame of reference.

Coherence

Agents are defined by their goal-directedness, but their goals need not be coherent. In fact, coherence is a key variable in characterizing an agent—how consistently it pursues its values, how unified its internal drives are, and how stable its behavior appears to others.

Humans, for example, often contain competing impulses. One part of us may want to maintain peak health; another seeks the immediate pleasure of potato chips. These internal contradictions mean we are not always aligned with ourselves, and our actions may oscillate or undermine long-term goals.

The same holds at larger scales. Nation-states and organizations can be modeled as agents, but their coherence varies. Russia, for instance, has strategic aims that justify treating it as a goal-directed actor in international affairs. Yet it would be a mistake to assume internal unity. The ambitions of citizens, factions, and institutions—and even contradictions within a single leader—make for a complex, sometimes incoherent composite agent.

Today's AI systems also exhibit this spectrum. In some sense present systems seem to merely simulate or imitate. They can be treated as agents in some contexts, but their behavior is often fragmented and sensitive to small differences in input—characteristic of low coherence.

Coherence in Value Space

In our picture of value space, coherence is represented by whether an agent’s vector directs to a narrow point or spreads across a broader region. Alice, a relatively coherent agent, occupies a tight cluster in value space. Bob-4.1, a less coherent AI, spans a wider volume—reflecting more diffuse, sometimes conflicting goals. Zooming out, we see that Alice and Bob are themselves sub-agents within the United States, which occupies an even larger region representing the diverse, often incompatible values of hundreds of millions of people.

The pattern is clear: the more incoherent the agent, the larger the volume it occupies in value space—pursuing different ends, sometimes at odds with itself.

Coherence brings advantages. Agents that consistently pursue specific goals tend to be more effective, much like a traveler who moves directly toward a destination instead of wandering along conflicting paths. But this same coherence can incur social costs. A tightly focused agent occupies a smaller region in value space, reducing overlap with others. This limits opportunities for mutual understanding and cooperation—and may increase the risk of irreconcilable conflict when highly coherent agents with incompatible values collide.

Power Differentials

Another critical dimension in multi-agent systems is the distribution of power. In our value space model, agents are represented as vectors pointing to regions (rather than points), with coherence determining the spread and alignment windows defining the bounds of tolerable value difference. Power adds another layer: it can be represented as the magnitude of an agent's vector. More powerful agents exert greater influence on their environment—and on other agents.

Just as there are alignment windows, there are power tolerances: ranges of power disparity that can be sustained without destabilizing the system or rendering weaker agents relatively powerless. When these tolerances are exceeded, systems risk collapsing into unipolarity or coercive imbalance. Power matters in both absolute and relative terms—though it is often relative differences that shape the strategic landscape.

Absolute Power Limits

Some capabilities may be too dangerous for any agent to hold, regardless of their values or intentions. For example, imagine a world where anyone with a laptop and $1,000 could use AI tools and mail-order gene synthesis to design and produce a highly infectious, highly lethal pathogen. In such cases, the problem is not inequality of power—it is the mere existence of the power itself that destabilizes the health of the system. Certain powers, once obtained, render coordination brittle or meaningless and it is in the interest of agents generally to ensure these powers are never obtained by anyone.

Relative Power and Stability

In practice, relative power disparities often matter more than absolute power levels. When differentials are extreme, conflict becomes cheap for overpowered agents and exploitation easier to justify or conceal. Even agents in perfect alignment have reason to ensure that power remains within tolerance. If Alice and Bob-4.1 are value-aligned, Alice still has little reason to cede all power to Bob. Her concern is not just present alignment, but future drift: her values could change, Bob’s could change, or their alignment may have been misjudged from the start. If Alice becomes relatively powerless, her interests are secure only insofar as their alignment remains perfect—and permanently so.

Moreover, power tends to concentrate. Agents are incentivized to gain power because it facilitates the realization of many other values. If an agent gains even a modest advantage—through luck, skill, or structural positioning—and if there is any opportunity to bring that advantage to bear in future competitions, it is incentivized to do so. Power used in one round can be leveraged to gain yet more in the next—each advantage stacking atop the last. When agents bring prior gains to bear in future competitions, their edge compounds, creating a feedback loop that amplifies disparities and entrenches dominance. This loop makes power accumulation the default trajectory rather than the exception—and enables dominant agents to block competition, as seen in monopolistic dynamics.

Further, this compounding dynamic introduces a structural incentive: agents who prioritize power acquisition—above cooperation, altruism, or restraint—are more likely to succeed over time. Sharing resources or failing to compete aggressively may shortchange an agent in future power competitions, reducing their ability to influence outcomes later. In systems where power can be repeatedly leveraged, advantage tends to accrue to those who seek it most directly. Unless such behavior is actively punished—through norms, regulation, or coordinated resistance—agents with selfish strategies may dominate by default, not because they are best aligned with collective goals, but because they are best suited to a compounding game.

Stability in multi-agent systems therefore requires deliberate constraints and checks against overwhelming concentrations of power—mechanisms for accountability, transparency, and upwards mobility.

Importantly, power also shapes value tolerance. When power is widely distributed, the alignment window can remain broad, accommodating a diverse range of agents. But as power concentrates, the window narrows—shaped disproportionately by the values of the most dominant actors. Both misalignment and power imbalance are therefore central sources of conflict.

On Conflict

Competition's Dual Nature

Competition between agents can enhance performance, offering benefits like improved sports training, product innovation, and evolutionary fitness—but these same forces risk destructive outcomes, prompting us to ask: how can we maximize the benefits of inter-agent conflict while minimizing the downsides? In particular, how do you tolerate diversity of values and goals in the world while ensuring stability?

To understand how conflict can be channeled constructively. Let’s look at the possible outcomes of conflict then turn to how agents reason about whether to engage in conflict.

Ways to War

Conflict between agents can produce a range of outcomes—some beneficial, others catastrophic. It's worth briefly taxonomizing the possible outcomes of competition.

There are Win-win conflicts: competitions that generate net benefits, either for both agents or for the broader system. In some cases, one agent wins and another loses, but society benefits overall—market competition drives innovation, academic rivalries yield discovery, and though only one researcher may be recognized, knowledge advances. In other cases, both agents benefit directly: two athletes training together may both improve in ways they could not by practicing against a training dummy. Win-win conflict is not the absence of struggle, but the structuring of struggle to produce surplus. Framed another way: these are conflicts that add value to the system, or are positive sum. Or put simply—they grow the pie. That said, cooperation often enables positive-sum outcomes as well, and a savvy system must weigh when competition versus cooperation is the more effective path to generating new value.

There are Win-lose conflicts: one agent's gain comes at another's expense. These include zero-sum disputes over finite resources, such as territory or budgets; competition for positional goods like leadership roles or prestige; and predator-prey dynamics, where survival is at stake. These conflicts may be necessary or even inevitable in some cases but they are worse in that they involve redistribution, not creation, of value. Win-lose conflicts are then zero-sum. They divide the pie.

There are Lose-lose conflicts: contests in which all participants end up worse off. Pyrrhic victories, arms races, and price wars fall into this category—agents expend resources not to win meaningfully, but to avoid losing ground. Cycles of revenge, mutual sabotage, or escalation-for-its-own-sake consume energy while degrading the system that sustains all participants. in value terms: lose-lose conflicts are negative sum, they consume value rather than producing or reallocating it. They shrink the pie.

The Will to Battle

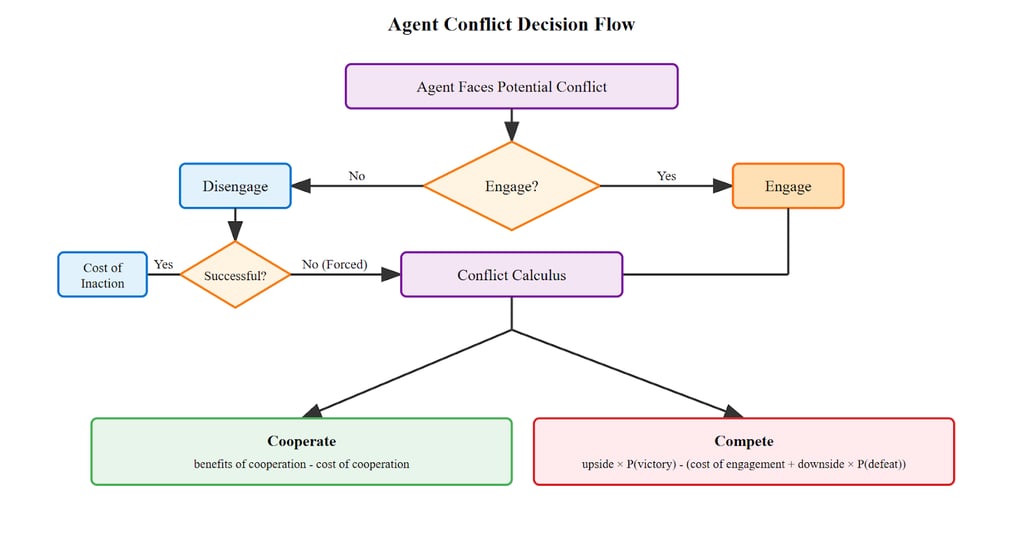

When agents face the prospect of doing battle, they perform a kind of conflict calculus—weighing the potential gains from victory against the costs of engagement and the risks of defeat, while also considering the cost of doing nothing. Inaction might mean ceding market share, allowing territorial expansion to go unchecked, or watching their values gradually lose ground in the world.

This reasoning can be abstracted as a choice between three strategies, where agents are incentivized to select whichever yields the greatest expected return:

Disengage = cost of inaction

Cooperate = benefits of cooperation - cost of cooperation

Compete = upside x P(victory) - (cost of engagement + downside x P(defeat))

Consider how this calculus plays out across a few examples:

Disengaging: A mid-sized retailer calculates that competing with a tech giant entering their market would cost millions with only a small chance of survival, making exit to an adjacent market their best option despite abandoning some existing customer relationships.

Cooperating: A senior researcher includes a junior colleague as co-author on a prominent paper in exchange for the junior researcher handling the time-consuming data analysis. Paying a marginal cost in recognition while boosting the junior colleague, the researcher spares themself some tedium.

Competing: A country weighs seizing a disputed region, estimating a reasonable chance of gaining valuable resources and strategic position, against the cost of engagement and the risk of economic sanctions if they fail. Large expected upside justifies the gamble, and so they mobilize.

This suggests some possible intervention points: we might make disengagement more viable, increase the attractiveness of win-win cooperation, or raise the cost of undesirable conflict. We’ll return to these and other possibilities later. For now, let’s continue to look at conflict and ask: how might conflict be constrained to promote stability and mutual benefit?

Civil vs Uncivil Conflict

Looking deeper, the conflict calculus reveals a second core choice agents must make: not just whether to compete, but how. The structure of conflict—the rules that govern it—profoundly shapes both its dynamics and its consequences.

There’s a useful additional delineation, based on how conflict and competition are staked. In particular, conflict can be divided into:

(a) holds barred, and

(b) no holds barred.

In holds barred conflict, agents agree to a shared code of conduct—mutually handicapping their full capabilities and competing only within a limited domain. Typically, this agreement is made in exchange for capped downside, under the assurance that both parties will abide by the same restrictions. This principle manifests at multiple levels. Individuals enter into Lockean social contracts, agreeing to abide by laws that prohibit theft, assault, and coercion in exchange for protection and the freedom to pursue their goals in peace. Organizations compete within frameworks of fair practice, channeling their rivalry into market performance, or service quality—burning hours and dollars, instead of buildings. Even states, in the most adversarial of conditions, can commit to international rules of engagement, e.g. the Geneva Conventions, hoping to limit the barbarity of war. With proper constraints and enforcement mechanisms, this civil form of conflict can in principle be used to minimize harm and preserve only the most beneficial forms of competition—maintaining agents’ ability to compete safely, giving them an avenue to vie for their values while protecting against the loss of their agency.

By contrast, when agents hold values that fall too far outside one another’s alignment windows—when the actualization of one agent’s values necessarily prevents the realization of another’s—mutually beneficial, rule-bound conflict breaks down. There is no room for compromise, because coexistence itself becomes impossible. If an existentially misaligned agent is defeated within the bounds of civil conflict, yet their agency remains intact (i.e. they are spared or left free) they must use what remains of their power to escalate the conflict. It’s a hill they are willing to die on. These are existential conflicts: maximum-stakes, winner-takes-all encounters that drag competition into its most brutal and unfettered form.

The distinction between civil and uncivil conflict maps cleanly onto different regions of value space, creating distinct zones that determine how agents are likely to interact based on their degree of alignment:

Alignment Window: The space in which agents hold differing values but can nonetheless coexist. Their goals are distinct but not mutually exclusive, allowing for tolerance and peaceful interaction. Put simply, You can have what you want, and it doesn’t get in the way of me having what I want.

Civil Misalignment Window: The space in which agents have conflicting values but are still willing to compete under some degree of constraints. They engage in rule-bound contests where coexistence is maintained through limited, structured conflict. Or, You getting what you want makes it harder for me to get what I want.

Existential Misalignment Window: The space where value systems are fundamentally incompatible—where the realization of one agent’s goals would preclude the realization of another’s. In this zone, agents may view the conflict as zero-sum at the level of survival or identity, and are willing to risk everything to prevail. Or, If you have your way, I’ll never have mine.

We can consider also how these alignment windows show up across different scenarios:

Within Alignment Window: A religious minority and secular majority coexist in the same country, content with their differing worldviews, respecting each other’s rights and freedoms within a shared legal framework.

Within Civil Misalignment Window: Two corporations launch competing products in the same sector. While their values and goals differ, they engage through marketing, pricing, and innovation—rather than sabotage or theft.

Existential Misalignment: A serial killer takes pleasure in ending lives. Their values directly violate the most basic condition of coexistence. So long as they remain free to act, others cannot safely pursue any conception of value. Coexistence is off the table.

In practice, agents may also engage in conflict improperly at an unnecessary or undesirable level, i.e. agents within the alignment window may still compete or civilly misaligned agents may compete with no holds barred due to failure of rationality, miscommunication, or poor incentives.

Agreeable Endgames

We mentioned that stability is a necessary property for multi-agent systems, but it is not sufficient. Not all forms of stability are desirable. Some solutions appear straightforward while collapsing under scrutiny, either because they fail to reflect practical constraints or because they come at too great a cost. As we think about the maintenance of society, it's useful to explore limit cases. I’d like to look at the dynamic of authoritarianism/libertarianism and analyze whether one of these endpoints represents a stable and agreeable endgame.

Free-Space (Libertarianism in the limit), — Systems which experience friction simply fracture into smaller systems rather than collapse. In environments where disengagement costs are trivially low—where space is effectively infinite, travel is cheap, and resources are abundant—agents may simply choose not to interact. If cooperation offers no clear benefit and competition carries risk, fragmentation becomes a natural choice. Agents can fracture into smaller self-contained systems or retreat into isolation. This misses the fact that many agents value sociality, continuity, or particular places—but it's a scenario worth considering. While we are currently constrained by Earth’s limited space and finite resources, we may soon stretch our legs across the stars. In the centuries ahead—and perhaps for millions of years thereafter—space may offer room enough for agents to simply spread out rather than coordinate tightly. The incentive landscape here is chiefly determined by physics and the nature of technological maturity. It may be that the wider universe allows defense to dominate. In this case disengagement cost is low because the splintering agent(s) will not pose a threat to the system in future. If however, physics in the limit allows for the creation of weapons which can pose a threat to even the most mature and distributed space-based civilizations—as imagined in, for example, the Dark Forest hypothesis—agents would be incentivized to disallow disengagement. This sets an upper bound on the degree to which libertarian visions are viable. Further, even for a defense-dominated universe in which you can allow civilizational splintering without threat of dystopian competition we should ask. Can libertarianism truly be taken to its extreme? Can we abide the pursuit of any values at all even if they do not infringe on the actualization of our own? It seems we could not condone everything. If a culture opts to disengage in order to instantiate worlds of eternal torture do we say, “sure, just not nearby our stars” or do we take up arms and say, “no you’re not doing it. Not in this universe. Not if we can stop it”? Hence while the dynamics of space-faring civilizations may be radically influential they do not seem to be able to do away with the need for coordination entirely.

Unipolarity (Authoritarianism in the limit), — Agents may be tempted to pursue unipolarity as a path to stability and value actualization. If coordination across many agents proves difficult, why not simplify the landscape—consolidate control, reduce friction, and ensure one set of values prevails? For those with power, unipolarity offers the promise of order and the opportunity to ensure that their values won’t be diluted, subverted, or lost. This possibility now seems alarmingly plausible. Advances in AI are rapidly generating unprecedented power differentials and absolute capabilities—possibly creating conditions under which a single actor, or system, could overpower all others. Takeovers like this may come in two major flavors:

Hegemon, — An agent goes unchecked and accrues power until they outcompete the system entirely. A variety of agents with a variety of goals exist but only the values of the hegemon are actualized.

Hive, — Agents compromise or converge to a single region of value and goal space, obtaining alignment sufficient to eliminate conflict and instability. Values become locked in, or values drift but divergence of values among agents is prevented.

We can recognize that such strategies might achieve stability, but they seem undesirable. The issue lies in the cost: peace is purchased through the erosion—or outright elimination—of agency. Under hegemony, your ability to pursue your values is constrained; your goals are realized only insofar as they align with the will of the sovereign. In the hive, you may persist as an agent, but not as the one you once were—your values supplanted by those of the collective. Taken together, free space and unipolarity represent limit cases of libertarianism and authoritarianism respectively. Here, hegemony and hive-minded convergence offer stability only by erasing agency, and free-space fails to obtain stability or permits the intolerable. Since we cannot simply pick a favored endpoint and take it to its logical conclusion we are forced to take on the hard task of striking a balance.

What kind of multi-agent system would we actually want to inhabit—not just survive, but flourish in? Agents benefit from the freedom to evolve their values, to set goals aligned with those values, and to retain the power to pursue them. Persistence across time—especially through uncertain futures—is instrumentally useful for nearly all objectives. Given that an agent’s current position is shaped by a mix of luck and circumstance, it is also advantageous to exist within a system that allows for recovery and upward mobility after failure. These are not merely moral intuitions, but rational design criteria: a stable system that protects agency and allows for positional mobility is one that agents will favor and aim to preserve under conditions of uncertainty.

If we understand the dynamics of agent coordination and iteratively refine models of societal stability, we can build distributed oversight systems with balanced power structures. Such prosocial frameworks can be designed for antifragility—flexing, adapting, and self-correcting not through suppression but through robust architecture. In this context, pluralism becomes an engine of progress rather than a liability. Divergent values drive exploration across the value landscape, generating innovations, strategies, and insights that homogeneous systems cannot achieve.

The challenge is not eliminating conflict but channeling it—ensuring that competition is bounded, cooperation is rewarded, and conflict does not escalate into irrecoverable loss.

Further, coordination at scale unlocks capabilities far beyond what any agent could achieve alone. It enables us to address shared risks, steward shared resources, and build worlds that no one tribe or faction could sustain. And if we care even minimally about others—whether from empathy, reciprocity, or shared vulnerability—then we ought to seek systems that offer all agents not domination or assimilation, but respect: the freedom to live, to try, to fail, and to try again. The requirements for agreeable endgames, then, are these:

Prosocial, — diverse agents cooperate, coordinate, and tolerate

Freedom-preserving, — agents meaningfully retain their values, goals, and power

Fair, — systems offer recovery, reintegration, and real opportunities for mobility

Stabilizing Multi-Agent Systems

Having explored the nature of conflict and competition dynamics, we can now turn to the question of intervention: What might promote stability in multi-agent systems?

If you, like me, are an agent aiming to actualize your values—and to persist, whether for instrumental reasons or as an end in itself—then stability is not merely desirable, but foundational. Without a stable environment, even the most coherent values and well-formed goals are rendered inert. Plans unravel, agency dissolves, and coordination collapses. Stability is what allows values to persist, cooperation to scale, and long-term outcomes to matter.

To build such systems, we must first understand what threatens them. Throughout this essay, we have examined alignment, coherence, power, and conflict—each offering distinct but interconnected pathways toward instability. From this, several key diagnostic dimensions emerge:

The degree to which the system is vulnerable to exogenous forces (i.e. how robust is the system of agents in the game of agents against physics/nature)

The degree to which agents in the system are aligned vs. misaligned

The degree to which agents are coherent vs. incoherent

The relative and absolute power levels among agents

The underlying incentive structures for agent interaction (e.g. disengage, cooperate, compete)

We might break this down in more detail.

Exogenous threats, — Non-agentic sources of existential risk such as cancer, pandemic, or asteroid impact, can pose an existential risk to an agent, a population of agents, or the system entire

Exogenous shocks, — Non-agentic disruptions, such as natural disasters or resource booms, can destabilize multi-agent systems even if they don’t harm agents directly by abruptly shifting incentives through environmental damage, infrastructure collapse, or sudden new opportunities.

Misalignment among coherent agents, — Highly coherent agents possessing incompatible values, come into conflict. Predictable pursuit of irreconcilable goals leads to intractable conflict or efforts at total suppression.

Conflict/chaos from incoherent agents, — Incoherent agents with unstable, self-contradictory, or poorly integrated goals behave unpredictably, undermining trust and disrupting systems that depend on stable expectations for coordination or deterrence.

Egregious absolute power, — Some levels of absolute power could be inherently destabilizing, particularly destructive capabilities that, if misused or mishandled, might threaten the continuity of the system itself.

Egregious relative power, — Severe disparities in power between agents incentivize powerful actors to employ coercion, and exploitation. Disempowered actors are incentivized to revolt if possible. Even when aligned in values, a weaker agent might act out of fear that the power imbalance will become permanent or misused.

High cost of disengagement, — Engagement rates increase causing agents to interact more frequently, and penalizing them for failing to cooperate or compete, possibly increasing overall the prevalence of conflict.

Unattractive cooperation, — Cooperation between agents becomes too costly or yields too little benefit, even mutually beneficial arrangements break down in favor of defection or fragmentation.

Cost of cooperation is high, — Negotiating and implementing cooperation requires substantial time, trust, or infrastructure—resources that not all agents can afford.

Benefits of cooperation are low, — If perceived payoffs from cooperation are minimal or uncertain, agents may prefer self-reliant or competitive strategies instead.

Attractive competition, — Competition becomes a dominant strategy when conflict is cheap, consequences are bounded, or rewards for victory are massive.

Huge upsides from conflict, — When particular conflicts offer overwhelming strategic, economic, or symbolic gains, agents are incentivized to pursue domination over coexistence.

Low risk conflict, — In environments where retaliation is unlikely or constrained—whether by norms, costs, or uncertainty—agents can engage in aggression with minimal fear of reprisal.

Low cost of engagement, — Asymmetric technologies make initiating conflict extremely cheap or there are few repercussions from initiating conflict, potentially raising the base rate of antagonistic behavior.

Capped downside, — Agents expect detriment from losing a conflict to be bounded and tolerable—due to, for example, legal protections, diplomatic restraint, or third-party mediation—they are incentivized to engage more freely in risky maneuvers.

Levers for Agent Coordination

This brings us then to outline categories of levers for improving agent coordination, organized by their underlying sources of instability, with examples to demonstrate that progress is achievable and within our control.

This framework helps to generate ideas and to clarify how proposed interventions might improve coordination among different populations—whether citizens of Norway, market sectors, US-China relations, AI agent systems, or human networks. Consider innovations that reshape the landscape using one or more of these levers. For each lever I present a few examples of previously successful or emerging interventions.

Misalignment Reduction —

Non-coercive consensus-building, e.g. Pol.is for digital deliberation

Improvements to information ecosystems e.g. community notes, and fact checking reducing conflict that arises from failure to agree on factual statements.

Incoherence Reduction —

Support agents in integrating stable values and resolving internal conflict, e.g. improving access to elite education; improving mental health via advancing psychology and pharmacology.

Alignment Window Expansion —

Consider or promote the adoption of expanded alignment windows to enable prosociality, e.g. pluralistic liberal norms that tolerate diverse values; institutional protections for minority worldviews.

Absolute Power Guarding —

Prevent destabilizing capabilities from emerging or proliferating, e.g. bioweapon research bans, nuclear nonproliferation.

Maintaining Tolerable Power Differentials —

Prevent domination and coercion via transparency and/or decentralized or centralized enforcement, e.g. antitrust law, watchdogs, checks and balances in government

Decreasing Disengagement Cost —

Make peaceful exit and reentry viable for agents and institutions, e.g. lower friction paths to exchange citizenship

Decreasing Cooperation Cost —

Lower friction in forming and verifying shared commitments, e.g. smart contracts.

Increasing Cooperation Benefits —

Amplify incentives for collaboration over competition, e.g. quadratic funding; retroactive rewards for public goods.

Limiting Conflict Upside —

Cap domination payoffs to discourage high-stakes escalation, e.g. staggering the rollout of advanced technology when sudden capability shifts enable first-mover domination; ceilings for resource extraction in contested domains.

Ensuring Civil Conflict is Low-Risk —

Make bounded, reversible competition the default with effective means to compete at low personal risk, e.g. elections, academic debate, market competition

Ensuring Uncivil Conflict Remains Costly —

Deter destructive escalation with clear consequences, e.g. automated retaliation protocols, decisive responses against defectors.

Capping Conflict Downside —

Reduce the severity of failure, e.g. income floors and safety nets; second-chance social infrastructure.

Protection from Known Exogenous Threats —

Build resilience to natural and systemic shocks, e.g. mRNA vaccine platform readiness, asteroid defense, AI-coordinated emergency logistics,

Research into Unknown Exogenous Threats —

Anticipate and monitor for black swan risks, e.g. biosphere anomaly detection; wildcard science grants.

Forecasting and Planning for Exogenous Shocks —

Invest in foresight and rehearsal, e.g. economic crisis simulations; forecasting, prediction markets.

Building Grand Futures

As a parting note, coordination problems are not simple. They are complex, multicausal, and deeply entangled with the values and vulnerabilities of the agents involved. They do not yield to silver bullets, nor do they resolve neatly under philosophical insight. But while the difficulty is real, so too is the opportunity.

At every stage of history, we catch glimpses of the branching tech tree—uncertain forks in the road that offer new powers, new risks, and new structures for how we live together. We choose which branches to climb. We choose how to develop our tools, how to shape them, how to weave them into the fabric of our societies. And these choices matter.

We have, I claim, the radical opportunity to steer this branching toward technologies that protect us, that are robustly good for diverse sets of agents, that balance power rather than entrench it. We can push on one another to keep that power in check—to distribute, rather than hoard, the light of willful agency. We can build systems that shape the incentive structures we face—nudging conflict into cooperation, zero-sum into positive-sum. We can build not just for survival, but to reach—together—for more: for more alignment, more abundance, more flourishing in a universe vast beyond imagining, laden with possibility.

There is no law that coordination must fail. Incentive structures can be reshaped. Norms can be rewritten. Defaults can be changed. We can build toward worlds where dictatorship is a sad and unsuccessful little strategy, where failure is not ruinous, and where the pursuit of one’s values does not require the suppression of others’.

This progress need not be utopian to be profound. We can move step by step—building, testing, iterating—just as we did before. The difference now is that we are growing up. We are running faster, acting on larger scales, and shaping systems that reach further into the future than ever before. We are powerful, but still vulnerable. The choices we make today matter more than they ever have—not just for ourselves, but for the trajectory of civilization. Let us build well, build fast, and build wisely toward a future for us and those who come after.

A future that is prosocial, free, fair.

A future that is stable,

for ages to come.

Additional References

Ngo, Richard. Towards a Scale-Free Theory of Intelligent Agency. Mind the Future, 2023. https://www.mindthefuture.info/p/towards-a-scale-free-theory-of-intelligent

Clifton, Jesse. Cooperation, Conflict, and Transformative Artificial Intelligence: A Research Agenda. Center on Long-Term Risk, 2020. https://longtermrisk.org/research-agenda

Dafoe, Allan, Edward Hughes, Yoram Bachrach, Tantum Collins, Kevin R. McKee, Joel Z. Leibo, Kate Larson, and Thore Graepel. Open Problems in Cooperative AI. arXiv:2012.08630, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.08630

Hammond, Lewis, Alan Chan, Jesse Clifton, Jason Hoelscher-Obermaier, et al. Multi-Agent Risks from Advanced AI. arXiv:2502.14143, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.14143

Sourbut, Oliver, Lewis Hammond, and Harriet Wood. Cooperation and Control in Delegation Games. Proceedings of IJCAI 2024. https://www.ijcai.org/proceedings/2024/26

Ngo, Richard. Elite Coordination via the Consensus of Power. Mind the Future, 2024. https://substack.com/home/post/p-159393313

Sam-V. Leviathan or Moloch on the State’s Role in the Economy. Medium, 2021. https://sam-v.medium.com/leviathan-or-moloch-on-the-states-role-in-the-economy-ef8fee016255

Alexander, Scott. Meditations on Moloch. Slate Star Codex, 2014. https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/07/30/meditations-on-moloch/